The Codependency Kate Blog

How to Self Regulate

All unwanted behavior comes from unmet needs. If we don’t view it this way, people’s behavior becomes fixed in our minds as labels or unhelpful beliefs about them. Eventually, this prevents us from connecting in relationships—with others, with ourselves, and most importantly, in how we parent our children in a connected, effective way.

We have a brain and a heart. Sometimes, when we process things only with our brain—by intellectualizing or ruminating—we get caught in unhelpful cycles and beliefs. This is often just unprocessed, unregulated emotion. It’s important to get in touch with how we feel about things, to get to the root of a behavior so we can understand it and then change it.

We can think of it like a house with a top floor (the brain) and a bottom floor (the heart).

The Brain-Heart House

When we’re stuck in our heads, looping over a problem, we sleep thinking about it, we wake up thinking about it, we talk to our friends about it. Our top floor becomes foggy. Overthinking, ruminating, pathologizing—these are all behaviors that come from dysregulation. Overthinking is a form of dysregulation. If we only stay on that top floor, thinking about the behavior, we end up creating core beliefs—about the situation, about ourselves, or about someone else.

The solution is to actually acknowledge your emotion. To figure out what’s really going on for you underneath the surface.

I talk more about how to get in touch with unmet needs and feelings in my other post on the BEND method.

Let’s explore what this looks like with an example.

Last night, my one-year-old went to sleep around 7:00 p.m. and woke up around 9:30 p.m. My husband and I split the night shift, and I thought I’d just settle her and put her back to sleep. But that’s not what happened.

I sat there with her, hoping she’d fall back asleep—but an hour passed, and then another. She was still awake.

I noticed myself—my behavior, my reaction. At first, I was okay. I enjoy one-on-one time with her. It was actually nice. I was watching TV, lying in bed, enjoying the snuggles. I wasn’t feeling inconvenienced, and I didn’t have unmet needs in that moment.

But by 10:45… then 11:45… she still wasn’t sleeping. By this point, I was feeling angry and frustrated. She was fussy, crawling over me, and I found myself getting mad at her—thinking angry thoughts about her.

At the same time, I was trying to figure out her behavior. Is she teething? Does she have a stuffy nose? What is she needing? I was in problem-solving mode—something we’re quite good at as parents. We constantly try to meet our kids’ needs. But I noticed that I was spinning: What’s wrong? What’s wrong?

That’s a symptom of my dysregulation.

So I stopped and asked myself: What am I feeling?

I noticed frustration, anger, tiredness, and exhaustion. And that awareness was the shift. I realized my anger wasn’t about her—it was about my own unmet needs.

When we’re dysregulated, we don’t have cognitive access to this kind of insight. So we have to sit with it.

And then it clicked—on a feeling level, from a deeper, wiser place: She’s one year old. She can’t take care of herself. This isn’t about her. This is about me.

What do I need?

Do I need a snack? Do I need to use the bathroom?

So I shifted focus from her to me and started problem-solving around my needs. I realized I was worried about sleep because I had work in the morning. It all made sense. My husband’s shift was supposed to start at 2:00 a.m., but by then, I’d already been at it for four hours.

I had reached my limit. I needed rest. So, I woke him up. I went to sleep. She fell asleep right after. Problem solved. No harm done.

All was good.

I woke up the next day, had six hours of sleep, and felt happy.

Why did everything turn out okay? Because I looked at my behavior and asked,

“What am I feeling? What do I need?”

If we don’t view behaviors—our own or our kids’—in this way, they turn into beliefs. In my head, I might have decided, “She’s just difficult,” or “I’m a bad mom.”

Our unprocessed feelings become facts in our minds. But the point of processing them is to create space for problem-solving. That’s what gives us direction. It’s how we stay connected i

instead of disconnecting—from ourselves, from our kids, or from our partners.

Resolution only happens when we allow ourselves to feel. Not just intellectualize.

It’s not about saying, “I’m angry—must be my trauma.” It’s about noticing, “I’m angry. Why? What are my unmet needs?” and then sitting with that.

Moving from intellectualizing to processing means shifting from “Why?” to “What?”

– Why is intellectualizing.

– What are my needs? That’s processing.

It takes time and practice. But it’s the most important skill.

Recommended Reading & Resources

There is so much information out there, it’s hard to know what’s what. Kate made this resource list to help. In it you’ll find books, podcasts, content creators, coaches, and organizations that share Kate’s values and beliefs as a licensed therapist.

Kate gets no kickbacks, commissions, perks, benefits, bonuses, or rewards for recommending any of these resources. She has no working relationship with any publishing house, authors, companies, content creators, coaches, or organizations. This resource list is a labor of love, from Kate, to help people find their way through the gray areas of life.

Self/Trauma

When I Say No, I Feel Guilty — Manuel J. Smith

The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook — Kristin Neff & Christopher Germer

No Bad Parts — Richard Schwartz

The Will to Change — bell hooks

Running on Empty: Overcome Your Childhood Emotional Neglect — Jonice Webb

The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self — Alice Miller

The Courage to Be Disliked — Fumitake Koga & Ichiro Kishimi

Untamed — Glennon Doyle

Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype — Clarissa Pinkola Estés

In Praise of Difficult Women — Karen Karbo

Be Ready When the Luck Happens — Ina Garten

Building a Life Worth Living — Marsha M. Linehan

Boundaries — Anne Katherine, M.A.

Wordslut — Amanda Montell

It’s Not Always Depression — Hilary Jacobs Hendel

The Easy Way to Stop Drinking Alcohol — Allen Carr

Complex Trauma: From Surviving to Thriving — Pete Walker

Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle — Emily Nagoski & Amelia Nagoski

ACEs —The CDC & Kaiser Permanente

Parenting / Reparenting

Unconditional Parenting — Alfie Kohn

Couples Counseling for Parenting — Stephen Mitchell, PhD & Erin Mitchell, MACP (Instagram)

Anything she’s ever written — Dr. Becky

Anything he’s ever written — Dan Siegel

Conscious Parenting — Dr. Shafali

Difficult Mothers, Adult Daughters: A Guide For Separation, Liberation & Inspiration —Karen C. L. Anderson

Daughters with Narcissistic Mothers: Dealing with a Self-Absorbed mother and Healing from Narcissistic Abuse. Recovering from Psychological Abuse and Emotionally Immature Parents — Alma S Bailey

Guiding Cooperative Children — Rachel Thomas

Marriage

Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love — Dr. Sue Johnson

Boundaries in Marriage —Henry Cloud and John Townsend

Mating in Captivity — Esther Perel

Nonviolent Communication — Marshall Rosenberg

How to Keep House While Drowning — KC Davis

Fight Right — John & Julie Gottman

Shameless — Nadia Bolz Weber

Come As You Are — Emily Nagoski

Come Together —Emily Nagoski

Family Systems

The Drama Triangle — Salvador Minuchin

Bowen Theory — The Bowen Institute/Dr. John Bowen

Children of Emotionally Immature Parents — Lindsay Gibson

Spirituality / Deconstruction

Wild Mercy — Mirabai Starr

The Forbidden Female Speaks — Pamela Kribbe

The Christ Within — Pamela Kribbe

Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving, and Finding the Church— Rachel Held Evans

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind—Yuval Noah Harari

Separation of Church and Hate: A Sane Person's Guide to Taking Back the Bible from Fundamentalists, Fascists, and Flock-Fleecing Frauds — John Fugelsang

Christian Resources

Boundaries in Marriage — Henry Cloud and John Townsend

Love Does: Discover a Secretly Incredible Life in an Ordinary World — Bob Goff & Donald Miller

Refer a Therapist

Have your own therapist and want to refer them to others? Click here!

Find a Therapist Like Kate

Parenting 101: BEND

This is the third post of my Parenting 101 series. We’ve been looking through the lenses of child development and family systems — and in this third part we’ll explore a crucial idea: your kids are not the cause of your behavior.

First, a quick recap of what we’ve covered so far. There are three phases of development: attachment, detachment, and connection. In Part 2 we talked about family roles: parents are always in a leadership role with their kids. The goal of development is to help your child lead themselves in their life while maintaining a connected relationship with themselves and with you. You lead by example: your kids learn by watching how you are with yourself, how you are in your relationships (especially marriage), and how you interact with them.

Kids are never on the same level as their parents. So anything they say or do is not supposed to be taken personally — because, to them, you are always their parent. Their behavior may reflect how you show up: your communication, boundaries, and the life you lead — but it’s not about your worth as a person.

In this post I’ll share my BEND method — a way to help parents understand their own behavior, process their emotions, and lead with clarity and compassion.

This is the third post of my Parenting 101 series. We’ve been looking through the lenses of child development and family systems — and in this third part we’ll explore a crucial idea: your kids are not the cause of your behavior.

First, a quick recap of what we’ve covered so far. There are three phases of development: attachment, detachment, and connection. In Part 2 we talked about family roles: parents are always in a leadership role with their kids. The goal of development is to help your child lead themselves in their life while maintaining a connected relationship with themselves and with you. You lead by example: your kids learn by watching how you are with yourself, how you are in your relationships (especially marriage), and how you interact with them.

Kids are never on the same level as their parents. So anything they say or do is not supposed to be taken personally — because, to them, you are always their parent. Their behavior may reflect how you show up: your communication, boundaries, and the life you lead — but it’s not about your worth as a person.

In this post I’ll share my BEND method — a way to help parents understand their own behavior, process their emotions, and lead with clarity and compassion.

BEND

The BEND Method — an overview

Parenting is, at its core, managing yourself. The better relationship you have with yourself, the better relationship you will have with your kid — because it isn’t compartmentalized. When you’re aligned, everything changes.

BEND stands for:

B — Behavior (and yes, B can also stand for Breathe)

E — Emotion

N — Need

D — Desire

We start with your behavior. All unwanted behavior — and in fact all behavior — comes from needs: met or unmet. The type of behavior signals whether those needs are being met. In short: all unwanted behavior comes from unmet needs.

Step 1 — Behavior (Pause and Breathe)

B: Behavior

If you notice yourself doing things you don’t want to be doing — yelling, contempt, disordered eating, substance use, shutting down — those are behaviors pointing to unmet needs. The first action is to pause. Breathe.

I like to say B can stand for Breathe because pausing gives you a break from reactivity and moves you from one-dimensional behavior into noticing. That noticing is the beginning of self-compassion.

Draw a simple stick figure in your mind — brain, heart, and soul. Our thoughts, emotions, intuition, needs and desires are the core. Behavior (our words and actions) is the expression. Too many parents stop at the expression and only try to fix the behavior. That’s one-dimensional and doesn’t heal the root.

Step 2 — Emotion (Name it)

E: Emotions

Once you’ve paused, ask: What am I feeling? Emotions are not meaningless — they are signals. There are many myths in our culture about emotions, and those myths keep us stuck at the behavior level. Naming the emotion reduces shame and begins to reveal the need underneath.

Step 3 — Need (Context matters)

N: Needs

Ask: What do I need right now? Context is everything. Behavior rarely appears out of nowhere — it has an adaptive function. It’s doing something for you, even if it’s unhelpful.

Example: You yell at the kids. Underneath you might be thinking:

I haven’t had a shower today.

My partner and I had a fight and it’s unresolved.

I’m exhausted because chores keep getting left undone — again (you did not take out the trash again).

If you hold the thought that your behavior makes sense in context, you can shift from shame (“I’m a bad parent”) to self-compassion (“I have unmet needs, and I can meet them.”). That shift is game changing.

Step 4 — Desire (Name what you want)

D: Desires

Once you know the need, ask: What do I want? Maybe you want calm. Maybe you want connection. Maybe you want boundaries respected. Naming your desire helps you act from leadership rather than reactivity.

When you meet your needs, you’re able to behave in ways that align with the leader you want to be. That’s self-leadership and self-regulation.

Modeling for your kids

When you practice BEND on yourself, you model the exact process you want your child to learn. If you believe your behavior comes from unmet needs, you can also assume the same for your child. Instead of taking their pushback personally, you can ask:

“What are you feeling?”

“What do you need, sweetheart?”

“I’m here. Let’s figure this out together.”

Example: “You don’t like the food that was cooked?” → “That makes sense. Tell me what you don’t like.”

Lead by example: breathe, name, meet needs where possible, and help your child do the same.

Important boundary: it’s not the child’s job to meet your needs

This is crucial. Your kids are not responsible for your emotional regulation. It is not their job to behave so you can feel okay. If you expect that, you’re reinforcing neglect of yourself. As a parent, your job is to put your oxygen mask on first: meet your needs so you can help your child meet theirs.

When you meet your needs, you remove the pressure from your child to perform emotionally. That frees them to develop without carrying your unresolved attachment issues.

A few real, practical moments

If you find yourself yelling: stop, breathe, name the emotion, ask what you need (maybe a shower, a break, a few minutes alone), and then respond from that grounded place.

If a child pushes away or rejects you during detachment: remind yourself that detachment is part of development and not a personal attack. You can feel the grief — parenthood is full of grief — and still lead with compassion.

If your marriage or a partnership is the source of ongoing stress: that’s work you need to do for your own nervous system so you can parent from presence rather than reactivity.

Bottom line

Behavior is a signal, not an identity. Your kids are not the cause of your behavior — your unmet needs are. Use the BEND method to notice (Breathe), name (Emotion), discover (Need), and orient (Desire). Do the inner work first; then model it for your child.

You can do this. We can do this together.

💬 Ask me in the comments: which part of the BEND Method do you want help with? Want a stick-figure graphic of the brain/heart/soul and the BEND flow? I can make one for you.

Parenting 101: Parent-Child Roles

Healthy parent–child relationships depend on clear boundaries, emotional maturity, and a strong parental leadership role. Many parents struggle with their child’s detachment phase because they haven’t resolved their own attachment wounds. This leads to guilt, shame, and unhealthy patterns in children. By understanding the family hierarchy, leading by example, and responding from a grounded, connected place, parents support their child’s development without blurring roles. Detachment is not rejection—it’s a natural stage that parents must guide with awareness, consistency, and emotional responsibility.

In part 1, we explored the three stages of development that your child should go through:

In their life, independent of you.

In their relationship with you.

These two are one and the same. The importance of detachment will be highlighted here to give you context. In this part, we will talk about boundaries in family systems and individuals.

Genogram

First, let’s look at family systems. This is called a genogram. A genogram is a visual that helps you understand your role as a parent. This is the dad and this is the mom. We are using a typical heterosexual relationship here for simplicity’s sake, not to be exclusive.

Do you see that the parents are not at the same level as the child? This stays this way until parents pass away. This power dynamic, where parents remain in their position, lasts until they pass. It never changes. It evolves, it transforms, but ultimately parents are always up here, and children are always down there.

This does not mean from an authority or dictatorship perspective. Parents mess up detachment when they misinterpret this structure—when they think being “above” means having power and control. On the other end, they also mess up when the roles are reversed, and the children are placed above them. This is permissive parenting.

The way to understand this system is through leadership. It is not about power, not about authority. Simply leadership. Bottom line: parents are in control of the child’s environment and development.

Parents with adult children often ask, “But my kids are grown up now. Aren’t we on the same level?” The answer is no. Parents are always one life stage ahead of their children—biologically, neurologically, and developmentally. They are always further along. And I will die on this hill: this is true.

When parents step into their power as parents, and truly accept their leadership role, everything in the relationship with their child transforms. The reverse, however, is not true. When a child becomes an adult and matures into the leader of their own life, it does not transform the relationship with the parent the way it does when the parent steps into leadership. Parents need to accept their leadership role—they are in it forever.

Now, where parents often go wrong in the detachment phase is when they themselves haven’t done their own work with their own parents. We see this often with estranged adult children. Parents will say, “I grew up and understood that my parents are human and made mistakes.”

But this is not an integrated point of view. They may have gone through development, but they haven’t done their emotional work. They haven’t learned from their parents’ mistakes in an integrated way. Otherwise, they would have empathy for their child, respect the detachment phase, and not be emotionally triggered by it. They might understand it cognitively, but not emotionally.

Parenthood is grief. If parents had done their own work, they would not carry the emotional charge that makes detachment feel so devastating.

Instead, what happens in most cases is that parents take it personally and feel rejected by their child. It feels like they are not valued as a person when their child detaches. This is because the parent is still stuck in the attachment phase. They have not moved through detachment themselves, so they cannot really connect with their child.

This harms the child deeply. The child ends up burdened with the parent’s unresolved emotional issues with their own parents. This leads to guilt and shame in the child, which often shows up as behavioral or emotional issues. They may find themselves in toxic relationships or repeating unhealthy patterns.

This happens subconsciously because parents have not led the way with awareness. As a result, children carry this pressure and responsibility without realizing it. They lose room for themselves in their own lives, and this comes out sideways in behaviors that don’t serve them—and that they don’t understand until they do their own work.

So what’s the most important thing for parents to learn?

The way children will learn detachment is by watching how you, as parents, live it out. That means:

You are living your life in a connected way. For example, in your marriage—if you are enmeshed or stuck in unhealthy patterns, you take responsibility for your part. That is the first thing to work on: your own relationships, your own patterns, and how this plays out in your life.

You lead by example, not just in your personal life, but also in how you respond to your kids when they bring their own issues to you. (We will explore this more in part 3.)

This is how parents reinforce their leadership role:

By leading by example—in their own life, with themselves, and with other people.

In the way they respond to their child, to each other, and to others.

By helping their child with their own issues from a detached, grounded parental role.

These three things must align and be in place:

How parents deal with their own marriage.

How they are with themselves: caring for their health, standing up for themselves, being kind and compassionate to themselves.

How they show up with others—partners, friends, extended family, work.

This looks like:

Living aligned in your own life.

Responding to your child in a grounded, connected way.

Helping your child with their own issues, without blurring the roles.

The main way parents screw up detachment is by taking things personally. When a child says or does something, parents respond as if the child is on their level, or as if they are friends. But children are never on the same level as the parent.

These three principles always apply.

Parenting 101: Attach-Detach-Connect

Parenting unfolds in three profound stages—Attachment, Detachment, and Connection—and each one quietly shapes the kind of relationship you’ll have with your child for the rest of your life.

In the beginning, attachment is everything. Your baby arrives hardwired for survival, clinging to you as their entire world. But attachment isn’t the same as connection. When parents mistake the child for an extension of themselves, attachment can slip into enmeshment—where the child absorbs the parent’s needs at the cost of their own.

Then comes detachment, the stage most parents struggle with. It’s the moment you begin seeing your child as a separate person, connected to you but no longer defined by you. This stage is uncomfortable because it asks you to let go. Yet it’s also the stage that protects the relationship long-term. When parents support healthy detachment, they prevent the resentment and estrangement that often surface in adulthood.

Finally, there is connection—the kind of relationship that isn’t built on dependency or fear, but on freedom and mutual respect. True connection can only exist when both attachment and detachment have been honored. It’s the moment your child becomes an adult who returns to you not out of obligation, but out of genuine choice.

Parenting is the hardest job in the world—and it is also the most important job in the world. So let’s get into it.

When we think about raising children, it helps to look at parenting through three key developmental stages: Attachment, Detachment, and Connection. Each stage shapes the kind of relationship you build with your child and influences how that relationship will look when they grow into adulthood.

Stage 1: Attachment

Stage 1: Attachment

The first stage of parenting is attachment.

This is what attachment looks like: them inside you.

It makes sense when you think about it. In the womb, your baby is surrounded by you. You are their entire environment. They feel everything you feel. It’s in their best interest to align with you.

When they are born, they come into the world with one survival instinct: to connect with their primary caregiver. That is the attachment phase.

But here’s the key: attachment is not connection. Attachment can actually slide into enmeshment, where the parent believes the child is an extension of themselves. Because children are hardwired to attach no matter what, they will often sacrifice their own needs to keep the parent’s approval—especially since they are legally and practically dependent until 18.

Stage 2: Detachment

Stage 2: Detachment

The second stage is detachment—and this is where most parents unintentionally go wrong.

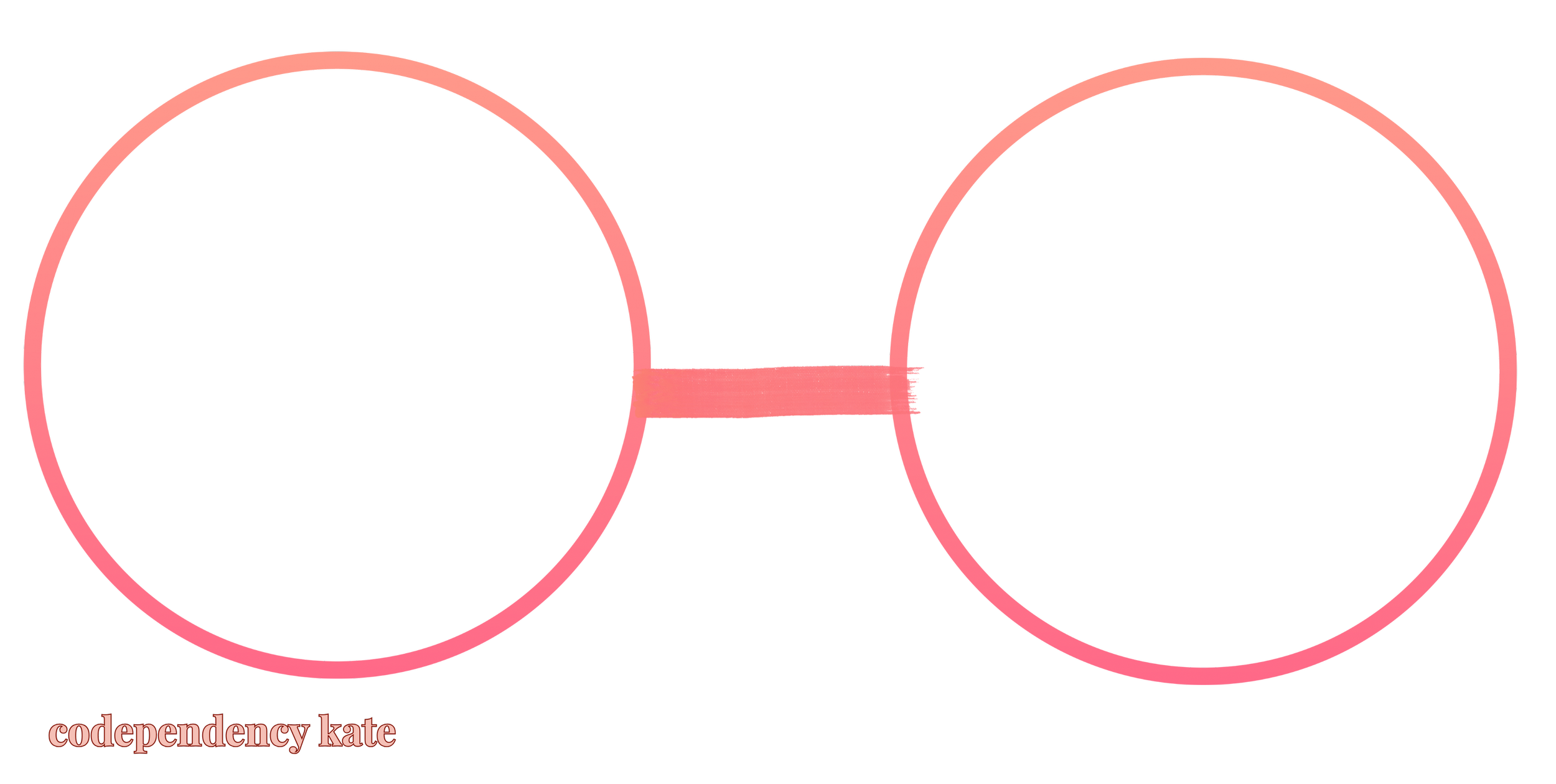

This is what detachment looks like: you and your child are two separate people, connected by a line.

In this stage, your child begins to separate physically and emotionally. They form their own boundaries, their own sense of self. This doesn’t mean disconnection—it means growth.

The scary part is that even with the best intentions, parents can mess this up. But here’s the truth: when you know better, you can do better. Supporting your child’s healthy detachment is the most important gift you can give, because it’s what prevents estrangement later in life.

Stage 3: Connection

Stage 3: Connection

The third stage is connection.

This is what real love feels like—not dependency, not control, but mutual respect and closeness. Connection is only possible when both attachment and detachment have been honored.

Healthy connection means your child grows into an adult who can return to you not out of obligation, but out of genuine love and choice.

Why Parents Struggle With These Stages

Many parents struggle to guide their kids through these phases because they haven’t experienced healthy attachment, detachment, or connection themselves.

We often see this in adult relationships: people stuck in anxious/avoidant cycles or the drama cycle where one partner over-functions and the other under-functions. This dynamic often shows up in heterosexual relationships, where women historically had to over-function for survival while men under-functioned due to cultural and economic realities.

From a family systems perspective, it all comes back to the partnership. The caregiver’s relationship with themselves and with their partner directly affects their ability to help their kids navigate attachment, detachment, and connection.

The Parenting Work is Also Self-Work

Here’s the truth: to help your kids move through these three phases in a healthy way, you have to practice the same process in your own relationships—whether with a partner, with friends, or even with yourself.

Even if you are a single parent, the principle applies:

Ask yourself, Are my relationships rooted in attachment survival? Do I allow for healthy detachment in my own life? Am I building true connection—or just clinging to attachment?

There is no judgment here. Wherever you are is valid. Parenting is about learning. The most important question to carry with you is this: